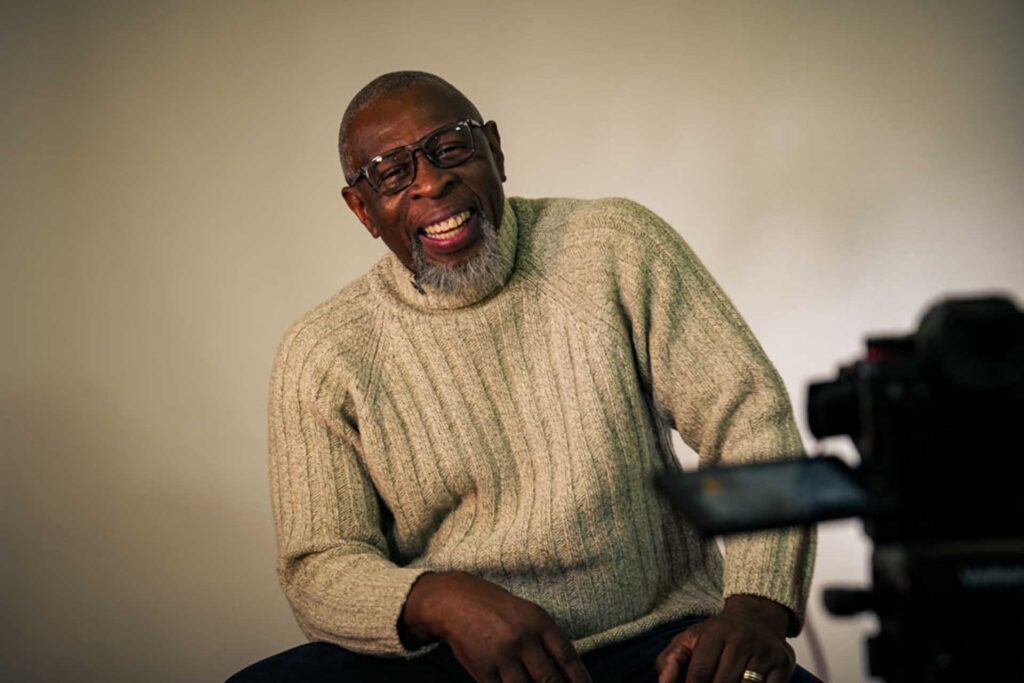

Irvin Lewis, from Walsall and one of 13 children, details a musical journey deeply shaped by his Jamaican heritage, Christian faith, and self-taught talent.

Initially believing musical ability was innate, not learned, he focused on observing and mimicking church musicians like David Copeland and Neville Clark on guitar and keyboards, as his family’s finances prevented formal lessons. He regretted avoiding formal music education due to the negative “label” associated with musicians at the time.

A significant shift occurred in college when he used his grant money to hire and eventually buy a saxophone, an instrument he loved and which was a “novelty” in church circles. This forced him to “find his own space” in musical arrangements. He learned by ear from instrumental artists like David Sanborn and Grover Washington, relying on a grassroots network of copied tapes from America and Jamaica. He cherishes the era when musicians brought instruments to church and learned “real time” on the spot, inspiring younger children.

Irvin asserts that the “black British gospel sound is unique,” a blend of American, Caribbean, and British influences, whose full potential remains largely unexplored. His professional life involved playing at his local church, with David Copeland’s band, and supporting artists like the Hawkins family at Aberdeen Street.

A recurring internal conflict was the church’s perception that being “too good a musician” was “worldly,” expecting him to eventually “put down your instrument and pick up the Bible.” This struggle led to a period where he felt God was telling him to stop playing, until he received a divine revelation that his gift was for God’s glory and he would be “charged for it” if he ceased.

After a five-year hiatus due to marriage and children, his passion was unexpectedly reignited by a friend’s request for saxophone on an album. A major setback followed when he suffered a stroke due to an undiagnosed brain tumor, resulting in paralysis of his right arm. His earlier divine encounter about using his gift became his driving force for recovery. Music became his “therapy,” improving his memory, concentration, and motor skills, leading him to volunteer in music therapy for the severely disabled.

Irvin now believes the next frontier for music is healing, urging the church to explore this aspect. He senses a “deep cry” from Caribbean ancestors, unique to those who experienced slavery, that he believes is “yet to be released” through their music. He praises the artistry of his peers, including Ray Prince, Dale Watson, Ian Reed, and Trevor Prince, and fondly recalls the “amazing” jamborees at Aberdeen Street and George Street that felt like American concerts to a young musician from Walsall.

His story is a powerful testament to faith, resilience, and the transformative power of music.

// Featured in

Born in Morgan's Pass, Clarendon, Jamaica, Sister McCalla demonstrated academic prowess, completing her sixth form and passing her first-year exams…

Raised in Moseley and Balsall Heath by Jamaican parents, George's early life was deeply rooted in the Church of God…

Born in Birmingham in 1960 to Jamaican parents, has an extensive history in music ministry, promotion, and community project leadership.

Louis Williams, a respected drummer and educator, shares a lifelong musical journey rooted in his Pentecostal upbringing in Willenhall and…

Alvin's bass journey began accidentally when his trombonist father bought a bass that "ended up with me playing it".

Maxine Brooks, born in Birmingham in 1964 to Jamaican parents, found her life's purpose in a Pentecostal church, leading to…